Paper II: Some common Features in Irish Gaelic and Hindu Societies

Liam SS Réamonn 8/Nodlaig/2005

[I] Mahatma Ghandi

[II] Evidence of Indo-European religious Links between Gaeldom and Hindustan

[III] Hindu Evidence of a direct Link with Celts

[IV] Folkloric Links

[V] Musical Links

[VI] The legal Systems

[VII] Enduring linguistic Connections

[I] Mahatma Ghandi

The long-lost comradeship between Celt and Hindu was evidenced when Mahatma Ghandi could say that he took inspiration in bringing about Indian independence from the struggles of the Irish people. Ireland , a country of insignificant extent, had caught the special interest of this great and spiritual leader. Originally the Celtic appearance in Europe , from near the Caspian Sea , came at the same time as another migration into India and Iran . It has been postulated that Proto-Celts and Hindus had a common ancestry in the Battle Axe People in southern Russia . Elements of pre-historic art still exist in the ethnic jewellery of India and Ireland .

Back to top

[II] Evidence of Indo-European religious Links between Gaeldom and Hindustan

Indo-European ancients, observing nature and drawing from its manifestations, deduced eternal truths with skill and in such manner as to give guidance and true meaning to the lives of generations to come. Gaelic and Hindu sagas are compelling. Hindu, Celtic, Teutonic and Greek mythologies contain the same conceptual groundwork. The powers of nature are given human form. Vedic brahmans and Celtic, Norse and Latin poets taught that the sky, sun, moon, earth, mountains, forests, seas and underworld were ruled by beings like their own temporal leaders but more powerful and subject to higher authority. Hinduism was materially influenced by the Kashyapa Buddha. It is, nonetheless, the only form of ancient Indo-European beliefs still widely practised. Orthodox Hindus today increasingly proclaim the universal Vedic truths. Gaelic ‘Vedic-type’ religion had no outside influence until the Gael adopted Christianity in 432 AD. Whilst much Indo-European tradition was then lost, it is still a factor, especially in Gaelic refuges (optimistically termed ‘Gaeltacht Areas’ or ‘Areas of Gaeldom’). Krishna , the Supreme Lord, is worshipped as the eighth Avatar of Lord Vishnu. His is an intensely human form, as described in Hindu epics. His exploits (‘Krishna Leela’) are a popular theme for artists. The Sanskrit root ‘krish’ means ‘existence’. In Irish, His name can perhaps be derived from ‘croí/croidhe’ (m, heart/core), with dental exchange in the final consonant of the old spelling. He was a manifestation of God’s love and existence, eternally free from the laws of matter, time and space.

Back to top

The following verses come from the Bhagavad-Gītā and reflect eternal truths:Chapter 2 (25): It is said that the soul is invisible, inconceivable, immutable and unchangeable. Knowing this, you should grieve not for the body. Chapter 4 (35): And when you have thus learned to speak the truth, you will know that all living beings are but part of Me [the Lord Krishna] - and that they are in Me and are Mine. Chapter 7 (6): Of all that is material and all that is spiritual in this world, know for certain that I [the Lord Krishna] am both the origin and the dissolution. Chapter 7 (22): Endowed with such faith, he seeks favours of the demigods and obtains his requests. But in actuality these benefits are bestowed by Me alone. Of the original northern Indian tribes, the Druhyu name corresponds to the Gaelic ‘draoithe’ (‘druids’). This root has survived with a certain semantic range in Germanic and Slavonic languages too. The Anus gave their name to the Irish goddess Anu (or Danu). Her (pre-Celtic) adherents, the Tuatha Dé Danann, went to live underground. They ruled from tumuli, perhaps a reflection of an earlier culture. The priestly class of the Anus, the BhRgu, may correspond to the Celtic goddess Brigit, whose tradition was Christianised, for preservation. The goddess’ spoked sun sign is as alive today in India as it is in Ireland . An association may also exist with the Rig-Veda, Bk 4, Hymn L: “Brhaspati, when first he had his being from mighty splendour in Heaven most supreme.” The Sanskrit for priest – ‘brAhmNa’ must bear a close relationship with the Irish ‘breitheamh’ (O Ir ‘brithem’) or ‘judge’. The Irish ‘curtha’ or ‘put’ may be cognate with the word Sanskrit itself - ‘samskrta’ or ‘put together/perfected’.

Back to top

[III] Hindu Evidence of a direct Link with Celts

Much of the interrelationship between Hindus and Gael comes from an exceptionally well guarded Indo-European heritage. A small example of direct Celtic in-put into Hindu culture, long after the two peoples had gone their separate ways, is the Sanskrit word for ‘war chariot’. Expanding political power, as well as long-distance trade, wrought cultural influences in the ancient world. U se of this particular word may reflect an anticipation of the wave of Celtic conquests, which came as far as Anatolia . Chapter 1 (24) of the Bhagavad-Gītā reads as follows: “Sa ñ jaya said, O descendent of Bharata, having been thus addressed by Arjuna, Lord Krisna drew up the fine chariot in the midst of the armies of both parties.” There is synonymy in PIE languages for ‘wheel’: the Greek ‘k ý klos’ and Latin ‘rota’ (O Ir ‘reth’). The ‘rota’ was an advanced, spoked wheel, dating from the start of the 2 nd millennium BC. The principle of morpho-semantic density makes ‘rota’ a Celtic word. In Sanskrit ‘rátha-‘ means ‘chariot’.

Back to top

[IV] Folkloric Links

Folklore shows that the ancient Irish were well aware of Asia . Gaelic mythology reaches far to the East, showing both old memories and how widely the ancients travelled. The first Irishman was a Scythian king called Fenius Farsa. He was overthrown and fled to Egypt . His son, Niul, married the Pharaoh’s daughter. They had a daughter called Scota. She in turn had a son called Goidel, after whom the Gael are called. In the 5 th century BC, Egypt was part of a Persian Aryan empire, which stretched as far east as the Punjab . Briciu Nemthenga (Briciu of the Poison Tongue) has been compared with Loki, a mischief-maker of the Germanic pantheon of gods. The story of the Feast of Briciu tells of the ‘Champion’s Covenant’ - the wager with the Bachlach (giant). He had gone through Europe , Africa and Asia , in search of Honour by making clever wagers.

Kali

Medb is one of the Celtic goddesses of dawn and dusk: her pyramid is in Sligo . Kuno Meyer and Heinrich Zimmer both thought this name to have been carried by an historical queen of Connacht . That is probably true. She probably donned the mantle of the legendary figure. The name has been related to the Sanskrit madhu (‘honey’ or ‘sweet drink’). Madhu is also one of the Daityas, a clan of evil spirits, who opposed sacrifice to the gods.

Female figures called ‘Sheela-na-Gigs’ (Sileadh na gCíoch) appear in Irish churches and castles of the 12 th to the 16 th centuries. Possible meanings for the carvings have been suggested, usually of a flighty nature. A 1996 National Museum booklet surmises that the figures represent an early Celtic or Indo-European earth-goddess. In 1979, a Sheela-na-Gig had featured in a French exhibition of Serbian archaeology, dating from 4500-4800 BC. People had probably come over from Anatolia , bringing idols of their deities.

Back to top

The statue of the Hindu goddess of destruction, Kali, is quite similar to a Sheela. The word Kali appears to be related to the Irish ‘Cailleach’ (shrouded woman). There is a Stone Age Cemetery, dating from 3200 BC, at Loughcrew in the county Meath . It comprises some 30 passage tombs. The cemetery is located on a hill. When the Celts arrived, they called it ‘Sliabh na Caillí’ – the Hill of the Witch of Death.

Indian folklore includes tales of humans taking on animal forms. In parallel, one of the Three Sorrowful Tales of Erin tells the Fate of the Children of Tuireann. There was enmity between Cian, the father of Lug, and the three sons of Tuireann. As he prepared for the battle of Mag Tuired, he saw them approach and, outnumbered, he changed his shape into a pig. Brian, having changed his brothers Iuchair and Iucharba into hounds, attacked and speared the pig. Cian asked to be returned to human form before he died. He was and was then slain. An éiric (blood fine) was placed upon the brothers. This included obtaining the ‘spear of Assal’ from the King of Iran.

Back to top

[V] Musical Links

Sitar music is composed as the musician plays. To gain mastery, he will study the instrument for twenty years. The sitar may have come to India in the 13 th century from Iran (seh – three, tar – string - as in guitar). The instrument was modified to cope with the idiom of the more ancient Indian music. The Irish harp is thought to have originated in Sumeria. It is three-sided and stringed. In 1603, the English Lord President of Munster , Henry Brouncker, ordered ‘the extermination by martial law of all manner of Gaelic bards, harpers etc.’ 5. Queen Elizabeth herself ordered Lord Barrymore to ‘hang the harpers wherever found’.

In music, the use of memorised patterns continues today in both India and Ireland . With Irish sean-nós (‘old method’) singing, songs, committed to memory, tell tales of long ago. This form of music is very old and, elsewhere in Europe , would appear only to persist in isolated parts of Sicily . The art form may share a common origin with Middle Eastern music. Again farther east, the slow, often mournful, Gaelic airs will resonate rhythmically with the melodic progression of traditional Indian music.

Back to top

Hindu hymn chanting has religious significance. Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu practised Kīrtana, teaching that the Hindu chants the name of the Lord Krishna, in the perspective that the name of the Lord and the Lord are not different. Fixing his mind on the Supreme Lord, he can attain Krishna consciousness. By carrying his meditation into daily life, he becomes a disciplined, focussed person. The ancient ‘Dord Fiann’ {the chant of Fionn Mac Cumhail and his warriors, ‘na Fianna’ (the Stags)} was perhaps such chanting, coming from the first stirrings of Indo-European wonder at the shining skys. (The Irish ‘spéir’ means ‘sky, beauty, brightness’.)

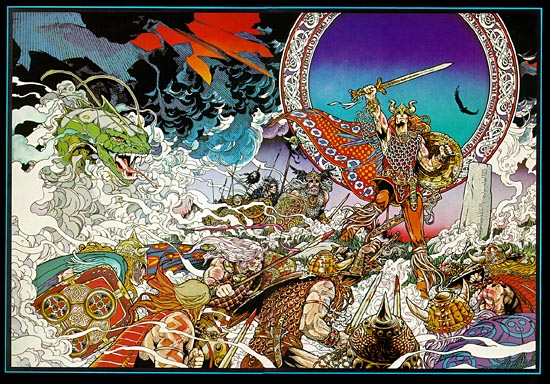

Nuada The High King ,

by Jim Fitzpatrick http://www.jimfitzpatrick.ie/

(C) 1977, Used with Permission

Back to top

[VI] The legal Systems

The Brehon laws are a repository of ancient legal procedures. Some of these date back 3,000 years. They were inherited or procured by Celtic wanderers from various members of the far-flung Indo-European family. It has been suggested that the ‘blush fine’ was an import from Asia . The Hindu practice of sitting dharma recalls ancient connections too. The Brehon laws have been criticised with all manner of lofty but shallow comment. Eoin Mac Néill wrote, in 1934, that even Ireland ’s enemies in the time of Elizabeth and James I noted the Irish love for law and justice 6.

Certain Gaelic and Hindu legal provisions 7 may be compared, as follows:

1) By Celtic law a man owed money could fast at the door of the debtor, who must join the fast, so forcing him to pay or enter arbitration.

By Hindu law, a creditor might fast at the door of the debtor, who was then obliged to protect the health of the creditor and pay the debt.

2) The Celtic Realm of all Life is called ‘bitus’ [cf the modern Irish phrase ‘ar bith’ (‘at all’)]. Gods are called ‘deuos’ (shining ones).

The Vedic earth-world is called ‘bhu’. Gods in the Vedas are invoked as ‘devas’ (shining ones).

3) There are Celtic deities for the natural forces, ethics, justice, knowledge, speech, arts, crafts, medicine, harvests, war, courage and battle against the forces of darkness. There are goddesses of land, rivers and motherhood. Gods often have a number of functions.

The Vedic pantheon includes deities for justice, rituals, ethical/ecological order, medicine, speech, arts, crafts, fire, solar, atmospheric and natural forces, harvests, war and battlers against malevolent beings. There are river goddesses. Gods often have a number of functions.

4) Druids studied for 20 years, in a strict discipline, to learn ritual laws and science.

Brahmans studied for 12 years in a gurukulan, to learn ritual laws, mathematics and astronomical science.

Back to top

Ireland operated a modified democracy under the Brehon Laws, which were advanced in concept. Like Vedic practices, they gave a strong legal status to women 8. The Brehon form compares with that of the legal system in 13 th century Asia , devised by the Mongol Genghis Khan, leader of the largest land empire ever won. The title Genghis Khan means ‘Oceanic Head’ –where ‘khan’ is cognate with the Irish ‘ceann’.

The Irish system comprised regulations on every aspect of life. As regulations were used, rather than a system of legal principle, it was not necessary to have a central authority, to which the kingdoms in Ireland , Scotland and the Isle of Man would not have given allegiance. The strength of the system was that it operated successfully throughout these allied but independent kingdoms, for nearly a thousand years.

The Common Law of Feudalism was imposed in Ireland , as a method of subjugation, when the Gaelic leadership had been exiled.

The constitutional system of Genghis Khan comprised a body of regulations called the Great Yasa (code). 9 There were regulations e.g. on taxation, the postal service, military inspections and unauthorised military leave. The Yasa saw a revitalisation amongst Uzbeks, Kazaks, Turkmen, Tajiks and northern Afghans in the 1500s. In the 1600s, the Genghisid lineages faded in Central Asia , some moving to India .

Back to top

[VII] Enduring linguistic Connections

Ireland and Hindustan are closer to their common origins than many people might expect. A very brief comparison between the Irish and Hindi languages - looking at basic structure, phraseology and vocabulary - provides additional firm evidence of this. Importantly, there was never a period of cultural decay such that an extensive innovation followed, to circumvent the loss of inflection and structure.

Prefixes and suffixes can tend to occlude the identification of root syllables. The final syllables of Indo-European words are inflected (to show case or tense) and, except for the patterns of change, are generally not useful for tracing connections.

The Romanised system is not sufficiently sensitive to the requirements of Hindi phonology. Modern Irish spelling is wanting as regards Irish phonology too. The linguistic comparisons made are based upon observation of the modern languages.

(i) Basic Structure

Many people will not have studied languages other than those of Aryan origin. Simple examples in Chinese (pinyin script) show that linguistic constructions come about, which are completely unfamiliar. Therefore any common usage in Irish and Hindi is not by chance but represents long-preserved connections.

- Verbs

Hindi: The suffix ‘nā’ is added to the root to form a verb: jānā: to go - ānā to come.

Irish: Verbal noun suffixes: ag glanadh (at cleaning), ag socrú (at deciding)

Chinese: There are adjectival or stative verbs, which do not change form. (Tense is normally shown by context.)

- Present Tense

Hindi: tu jāta/jāti (m/f) hai: you go (auxiliary verb used)

yahāń ek khān hai: there is a mine here

yah an de bahut ķare haiń: these eggs are too hard (note the plural verb form)

tu ja raha hai: you are going (continuous present)

Irish: tá an ghaoth láidir: the wind is strong

tá na huibheacha briste: the eggs are broken

táimid ag rith: we are at running (auxiliary verb ‘to be’ used with

continuous present)

Back to top

- Perfect and Future Tenses – Hindi, Irish and Chinese

Hindi Past Perfect: A transitive verb agrees with the object, in number and gender.

Intransitive Perfect: woh bolā: he spoke Past Perfect: woh bolā hai: he has spoken (auxiliary verb used) Transitive Perfect: us ne das ghore dekhe: he saw ten horses

Irish:rinne sé a dhícheall: he did his best - ní dhearna siad a ndícheall: they did not do their best (dependent form of the verb)

Hindi and Irish: maiń dūngā: I shall give - tabhairfaidh mé: I shall give

(Latin ‘dare’ is evident.)

Chinese: wŏ māng: I [was/shall be/will be/would have been etc.] busy

tā hĕn māng: he very busy

wŏ māng míng tiān: I busy tomorrow

wŏ māng hoù tiān: I busy day after tomorrow

Imperative – Hindi, Irish and Chinese

Irish does not have an Imperative of Respect, which is an exceptional feature in Hindi. Normally, Hindi uses the plural form of verbs as the polite form – comparable with most European tongues. Irish has the same system as Latin – one form for the singular and one for the plural. The use of special polite forms is difficult for Irish people to grasp. All of Gaelic society has a strong sense of close brotherhood.

Back to top

Hindi: jā: go (thou) - ā: come (thou) - jāo: go (thou) - āo: come (thou)

jāie: (please) go - āie (please) come - mere būt utāro aur silpat lāo: take off my

boots and bring me my slippers

Irish: imigh: go (thou) - imigí: go (ye)

Fág salach an fhuinneog agus ní fheicfidh tú mórán: leave (thou) dirty the window and you will not see much.

Chinese: A tone-of-voice word (‘ba’) is added to the end of a sentence to indicate a command: Qĭng hē yì-diăr chá ba: please drinking little bit tea OK!

Nouns – Irish, Hindi and Chinese

Irish and Hindi have lost the neuter gender. Nouns are defined as masculine or feminine. They are declined: Hindi uses two of the original Indo-European eight cases. Modern Irish uses five. Old Irish had a locative case, still seen in place-names.

Chinese nouns are not declined (pronouns change in the plural). They are given no gender. There are no definite or indefinite articles. Unlike Hindi and Gaelic, there is no correspondence with adjectives either. Meaning, again, is given by context. Certain grammarians see dropping grammatical rules as a sign of linguistic development. This is, perhaps, because synthetic Indo-European languages have dropped most of the rules on inflection. The argument is fallacious: Lăo péng-you: an (the) old friend(s); to, with, of, by or from an (the) old friend(s) etc.

In both Hindi and Irish, consonants may be aspirated. In Irish, lenition of initial consonants may be reversible, in order to show a change in case or tense. As in the case of Irish, German and Arabic, Hindi has long and short vowels.

Back to top

(ii) Phraseology - Questions in Hindi, Irish and Chinese

An intonation of voice is used in Hindi and Irish.

Hindi: yah strī kaun hai? who is this woman?

kitne din lageņge? how long will it take?

Irish: The verb (in the dependent form) is preceeded by the word ‘an’:

an bhfuil siad ag teacht? are they atcoming?

Chinese: The sentence stays the same: there is no change in intonation. The tone-of- voice word ‘ma’ is added to show the speaker wants information. (The tone of Chinese syllables already determines their meaning.)

Tā huì shuō Zhōng-guo huà ma? He able speaking China words yes?

(iii) Vocabulary

A list of some eighty-five comparable leximes found in modern Irish and Hindi is shown below. The words point to a more extensive vocabulary of common origin. The only real connection between Irish and Hindi is from the original Indo-European. Below, etymological processes are suggested to indicate possible changes in words.

Back to top

Irish

|

Hindi |

croí/croidhe (m, heart/core – dental exchange)

aon (one)

dó (two)

trí (three)

ceathar (four)

cúig (five)

sé (six)

seacht (seven)

ocht (eight)

naoi (nine)

deich (ten)

dhá uair (twice, bh = v, w)

ainm (name)

anaithnid (unknown)

athair (father - Latin pater)

báigh (to drown)

bard (bard)

barr (top)

bláth (flower)

bodhar (deaf)

bráthar (brother, kinsman)

cad (what?)

cá háit (where? - see German ‘ort’)

cathain (when?)

cé (who?)

ceo (fog)

cill (church)

clann (family)

crann (tree)

cruaidh (hard)

chuaigh (went)

claoi (ditch)

cuan (harbour)

dáil (to distribute)

dána (brave, enterprising)

deachar (difficult)

díomách (disappointed)

dorcha (dark)

dord (chant)

duairc (gloomy)

dubh (dark, miserable)

eallach (cattle)

fáil (to find – aspiration and dental exchange)

fás (to grow)

gadhar (dog)

garbh (rough)

gob (beak, mouth)

gráinn (hate)

gual (coal)

labhairt (to speak)

lobhtha (rotten)

log (a place – of people)

mallaithe (vicious)

marbh (dead)

máthair (mother)

meon (mind)

mór (big)

nocht (naked)

oilithreacht (pilgimage – loss of initial t)

an t-ola (the oil - initial t reversible)

pár (parchment)

paróisde (parish)

poc (goat)

poll (hole)

príomh- (prefix – ‘of first place’)

rang (row, line)

saibhir (wealthy)

sámh (pleasant)

samhlú (to imagine)

sásta (satisfied)

seomra (room)

snámh (to swim)

socrú (to decide)

solas (m light)

sona (happy)

striapach (harlot)

tafann (bark, noise)

tír (country)

tóchar (tunnelled drain)

tóir (trail)

torann (noise)

uair (hour – loss of initial g)

uain (lamb)

údar (authority - original giver, úr + Latin dare)

uisce (water) os (dew),

|

Krishna the Supreme Lord, eighth avatar of Vishnu

ek (one)

do (two)

tīn (three)

chār (four)

pānch (five - see Welsh ‘pump’, q to p)

chhe (six)

sat (seven)

āth (eight)

nau (eight)

das (ten)

do bār (twice)

nam (name)

anāth (orphan)

pitā (father)

bā dh flood

bhāţ (bard)

barā (great)

phūl (flower – b to ph, epenthetic vowal)

baharā (deaf)

bhāí (brother, lost r)

kyā (what? – aspirate ‘d’)

kidhar (where?)

kab (when?)

kauņ (who? – lose nasal ‘n’)

kohra (fog)

kīlā (fort)

kul (family – epenthetic vowal)

pēŗ (tree – q to p, epenthetic vowal)

karā (hard), krodh (anger)

gayā (went)

khāī (ditch)

kuāń (well)

dalāl (broker)

dhanī (rich)

dushkar (difficult)

dhīmā (slow)

andhera (dark)

dhol (drum – dental exchange)

darnā (to be afraid)

dukhī (miserable)

galla (herd – initial loss of g)

pānā (to find)

fasal (crop)

gadha (donkey)

garj (thunder)

gap shap karnā (chat)

ghrinā (aversion, disgust)

koelā (charcoal, coal)

bolnā (to speak – metathesis)

lobh (avarice)

log (people)

mailá (dirty)

mar jānā, marnā (to die)

māņ (mother)

man (mind)

motā (fat)

naņgā (naked)

tīrthyātrī (pilgim – metathesis, exchange of dentals)

tel (oil)

parhnā (to read)

parosī (neighbour)

bakrā (goat)

polā (hollow)

prem karnā (to love: príomh ~ prem)

rang (colour, line in the rainbow)

sabhya (polite)

sāf karnā (to clean)

samajhnā (to understand)

sastā (cheap)

kamara (room)

snān karno (to have a bath)

sochnā (to think)

sulgānā (to light), sūraj (sun)

sundar (beautiful)

strī (woman)

tūfānī (stormy)

tīr (coast, arrow)

tokrí (basket – its shape the root meaning)

talāsh (search – dental exchange)

tornā (to break)

gharī (clock)

ūņ (wool - metonymy)

udar (generous - original giver)

bhistī (water-carrier)

|

1 The Celtic Origin of Latin ‘rota’, by Mario Alinei - Studi Celtici, 2001

Celtic Myths and Legends by Charles Squire – Parragon, 2000

A Guide to Irish Mythology by Daragh Smyth - Irish Academic Press, 1998

The Atlantean Irish by Bob Quinn - The Lilliput Press, Dublin . 2005

5 The Irish Harp Emblem by Séamus Ó Brógáin - Wolfhound Press, 1998

6 Irish Laws by Mary Dowling Daley (The Appletree Press, 1989)

7 Hinduism Today, May 1994

8 A Guide to early Irish Law by Fergus O’Kelly, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2001

9 Lecture by Prof. Robert D McChesney - New York University , 1997

Back to top